Introduction: Understanding the West Nile Threat

West Nile Virus (WNV) has emerged as one of North America’s most significant mosquito-borne diseases over the past two decades. Once unknown in the Western Hemisphere, this virus now represents a seasonal epidemic that flares up each summer and continues into fall. While most people infected with WNV experience no symptoms, some develop serious and potentially life-threatening illnesses, making public awareness crucial.

This comprehensive guide explores West Nile Virus in detail—covering its origins, transmission, symptoms, treatment options, prevention strategies, and the latest research. Whether you live in a high-risk area or simply want to protect yourself and loved ones, understanding this disease is your first line of defense.

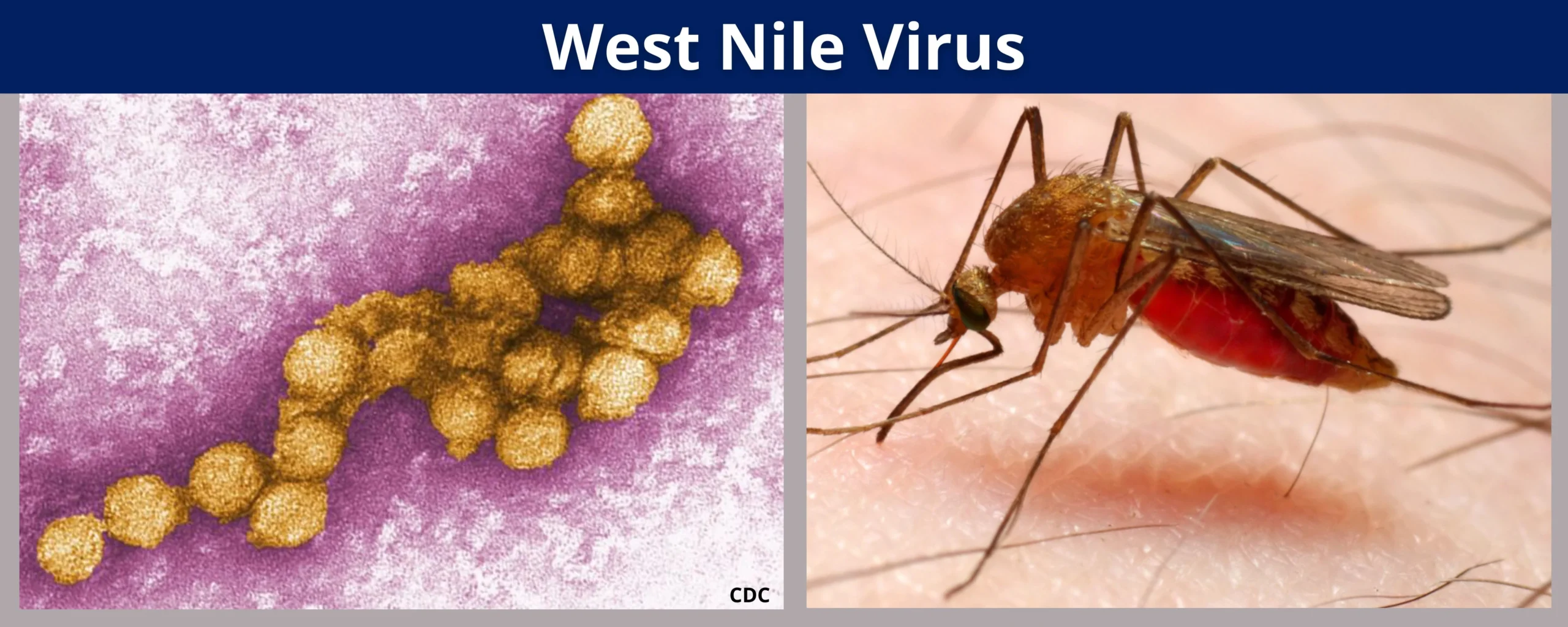

What Is West Nile Virus? Definition and Basic Facts

West Nile Virus is a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Flaviviridae family, which includes other notable pathogens like dengue, yellow fever, and Zika viruses. As a member of the Japanese encephalitis virus antigenic complex, WNV primarily circulates between birds and mosquitoes, with humans and horses serving as “dead-end” hosts—meaning that while they can become infected, they typically don’t develop sufficient viral loads to spread the disease further.

Key facts about West Nile Virus include:

- Transmission: Primarily spread through the bite of infected mosquitoes, particularly those of the Culex genus

- Seasonality: Most common during mosquito season (summer through fall) in temperate regions

- Infection rate: Approximately 80% of infected people remain asymptomatic

- Serious cases: About 1 in 150 infected people develop serious neurological illness

- Risk groups: Adults over 60 and people with certain medical conditions face higher risks of severe disease

- No human vaccine: Unlike some other mosquito-borne diseases, no human vaccine is currently available

- No person-to-person spread: The virus does not spread through casual contact with infected individuals

Historical Origins and Global Spread

West Nile Virus was first isolated and identified in 1937 from a woman with a febrile illness in the West Nile district of Uganda—hence its name. For decades, it remained relatively obscure, causing occasional outbreaks in Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Europe, but rarely drawing international attention.

The virus’s global history includes several key milestones:

- 1937: First isolation in Uganda

- 1950s-1980s: Sporadic outbreaks in Israel, Egypt, and parts of Europe

- 1996: Major outbreak in Romania with high rates of neurological disease

- 1999: First appearance in North America, with an outbreak in New York City

- 2002-2003: Dramatic expansion across North America, becoming the largest arboviral disease outbreak in U.S. history

- 2012: One of the largest U.S. outbreaks, with 286 deaths

- Present day: Now endemic in Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and North America

The introduction of West Nile Virus to North America in 1999 is considered one of the most significant events in emerging infectious diseases of the past century. Within just five years of its arrival, the virus had spread across the continental United States and into Canada, Mexico, and parts of the Caribbean.

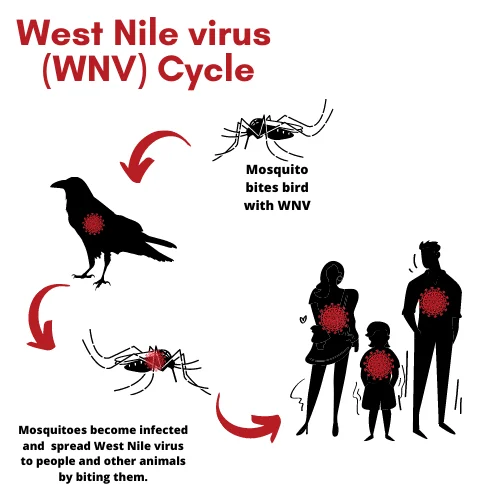

Transmission Cycle: From Birds to Mosquitoes to Humans

West Nile Virus maintains a complex transmission cycle in nature:

Primary Cycle

- Birds serve as the primary amplifying hosts, developing high levels of virus in their bloodstream

- Mosquitoes (primarily Culex species) become infected when feeding on infected birds

- The virus replicates in the mosquito’s gut and salivary glands over 1-2 weeks

- Infected mosquitoes then transmit the virus when taking subsequent blood meals

Secondary Transmission

- Humans and horses become infected when bitten by infected mosquitoes

- These are considered “incidental” or “dead-end” hosts because they don’t develop sufficient viremia (virus in bloodstream) to infect feeding mosquitoes

- Bird-to-bird transmission can occur through direct contact in some species

- Rare alternative routes in humans include:

- Blood transfusion (very rare since blood screening began in 2003)

- Organ transplantation

- Mother-to-child transmission during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding

- Laboratory exposure

The virus’s ecology is deeply tied to bird migration patterns, which helps explain its rapid spread across North America following introduction.

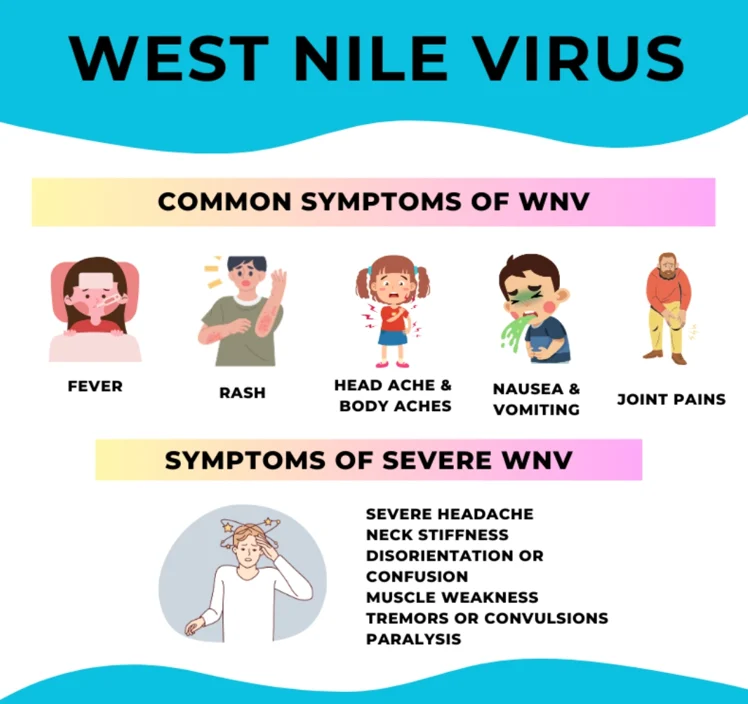

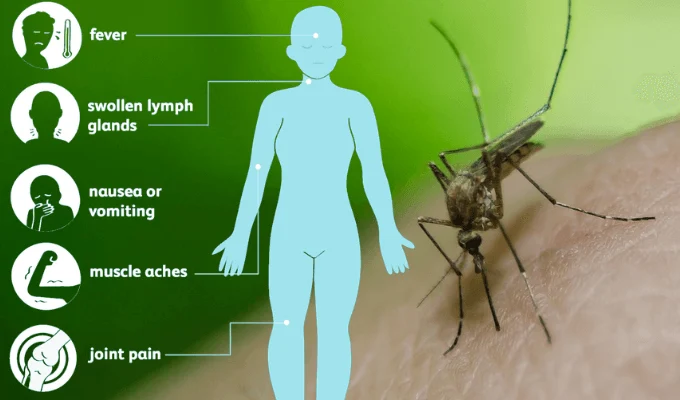

Symptoms and Disease Progression: From Mild to Severe

West Nile Virus infections manifest across a spectrum of severity:

No Symptoms (Asymptomatic Infection)

- Approximately 80% of infected people develop no symptoms

- These individuals only discover their prior infection if tested for WNV antibodies

West Nile Fever (Mild Illness)

About 20% of infected people develop a febrile illness with symptoms including:

- Sudden onset of fever

- Headache

- Body and joint aches

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Fatigue

- Skin rash (usually on the chest, stomach, and back)

- Swollen lymph nodes

These symptoms typically appear 2-14 days after infection and can last from a few days to several weeks. Most people with West Nile fever recover completely, though fatigue may persist for weeks.

Severe Neuroinvasive Disease

Approximately 1 in 150 infected people develop serious neurological complications, including:

- West Nile Encephalitis: Inflammation of the brain, causing:

- High fever

- Headache

- Neck stiffness

- Stupor or disorientation

- Coma

- Tremors or seizures

- Paralysis

- Vision loss

- West Nile Meningitis: Inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord, causing:

- High fever

- Headache

- Stiff neck

- Sensitivity to light

- Confusion

- West Nile Poliomyelitis: Inflammation of the spinal cord similar to polio, causing:

- Sudden weakness

- Flaccid paralysis

- Breathing difficulties if respiratory muscles are affected

Recovery from severe neuroinvasive disease may take weeks or months, and some neurological effects may be permanent. The mortality rate among patients with neuroinvasive disease is approximately 10%.

Risk Factors: Who’s Most Vulnerable?

While anyone can become infected with West Nile Virus, certain factors increase the risk of both infection and severe disease:

Risk Factors for Infection

- Living in or traveling to areas with active WNV transmission

- Outdoor activities during peak mosquito hours (dusk and dawn)

- Occupations requiring extensive outdoor work

- Poor housing conditions (lack of window screens, standing water nearby)

- Season (late summer and early fall in temperate regions)

Risk Factors for Severe Disease

- Age: Adults over 60 have the highest risk of severe illness

- Medical conditions: Individuals with certain conditions face increased risk:

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Cancer

- Kidney disease

- Organ transplant recipients

- Those taking immunosuppressive medications

- Genetic factors: Certain genetic variations may increase susceptibility

Understanding these risk factors helps identify vulnerable populations for targeted prevention efforts and heightened clinical vigilance.

Diagnosis: Confirming West Nile Virus Infection

Diagnosing West Nile Virus requires laboratory testing, as its symptoms often resemble those of other viral illnesses. Healthcare providers typically consider WNV when a patient presents with unexplained fever, neurological symptoms, or both during mosquito season in areas where the virus is active.

Diagnostic Methods

- Serological Testing:

- IgM antibody detection: The most common test, detecting recent infection

- IgG antibody detection: Indicates past infection

- Plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT): Confirms and distinguishes WNV from related viruses

- Molecular Testing:

- PCR (polymerase chain reaction): Detects viral RNA in blood or cerebrospinal fluid

- Most useful during early infection before antibody development

- Other Laboratory Findings:

- Cerebrospinal fluid analysis often shows elevated white blood cell count and protein levels in neuroinvasive cases

- Blood tests may reveal mild elevation in liver enzymes

- Neuroimaging:

- MRI or CT scans may show abnormalities in brain tissue in encephalitis cases

Diagnosis often requires multiple tests and consideration of clinical symptoms, travel history, and exposure risk. Timing is crucial, as viral RNA is typically detectable only during the first week of infection, while antibodies may take 8-14 days to develop.

Treatment Options: Managing West Nile Virus Infection

Currently, no specific antiviral treatment exists for West Nile Virus infection. Management focuses on supportive care to help patients through the course of the illness:

For Mild Cases (West Nile Fever)

- Rest and adequate hydration

- Over-the-counter pain relievers like acetaminophen or ibuprofen for fever and discomfort

- Avoidance of aspirin in children and teenagers due to risk of Reye’s syndrome

- Symptomatic treatment of specific complaints

For Severe Neuroinvasive Disease

- Hospitalization is typically required

- Intravenous fluids to maintain hydration

- Respiratory support, potentially including mechanical ventilation in severe cases

- Prevention and treatment of secondary infections

- Anti-seizure medications if needed

- Intensive care monitoring for complications

- Physical therapy during recovery phase

Investigational Approaches

Several experimental treatments have been studied but none have definitively proven effective:

- Intravenous immunoglobulin containing WNV antibodies

- Interferon alpha-2b

- Ribavirin (an antiviral drug)

- Various monoclonal antibody therapies

Research continues on potential antiviral medications and immunomodulatory therapies, but proven options remain limited.

Long-term Effects: Beyond the Acute Illness

While most people with mild West Nile fever recover completely, those who develop neuroinvasive disease may face lasting health effects:

Potential Long-term Complications

- Persistent neurological deficits: Including weakness, cognitive impairment, and movement disorders

- Post-infection fatigue syndrome: Debilitating fatigue lasting months or years

- Memory problems and difficulty concentrating

- Depression and mood disorders

- Physical disabilities requiring ongoing rehabilitation

- Vision or hearing problems

Studies tracking long-term outcomes have found that:

- Approximately 40% of patients with neuroinvasive disease report symptoms persisting 8-12 months after infection

- Some patients never fully recover their pre-illness level of functioning

- Quality of life may be significantly impacted even years after infection

The economic burden of these long-term complications, including healthcare costs and lost productivity, underscores the importance of prevention efforts.

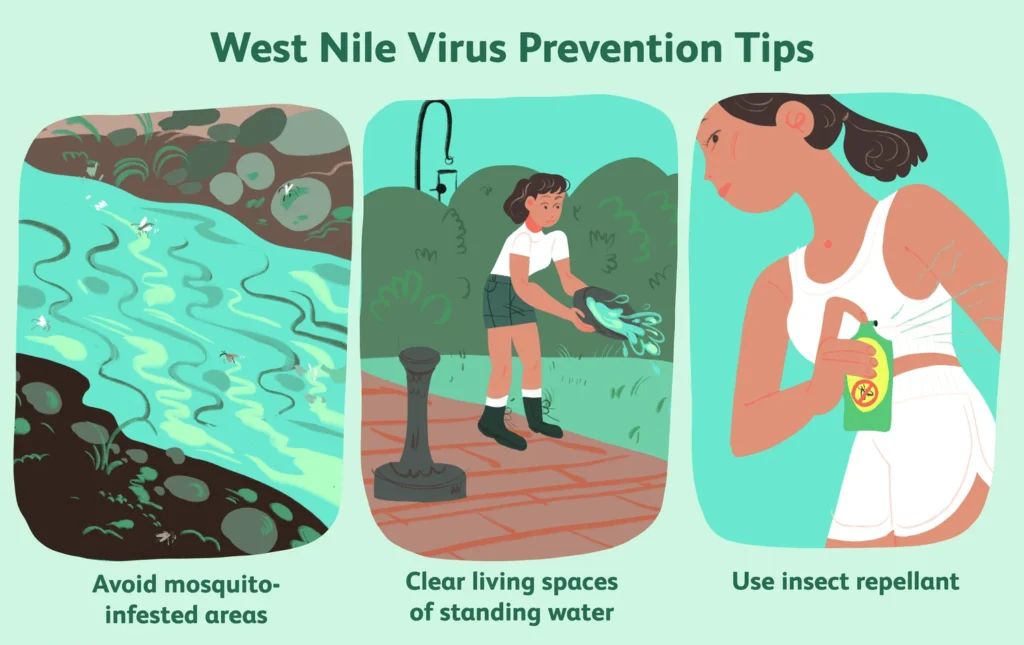

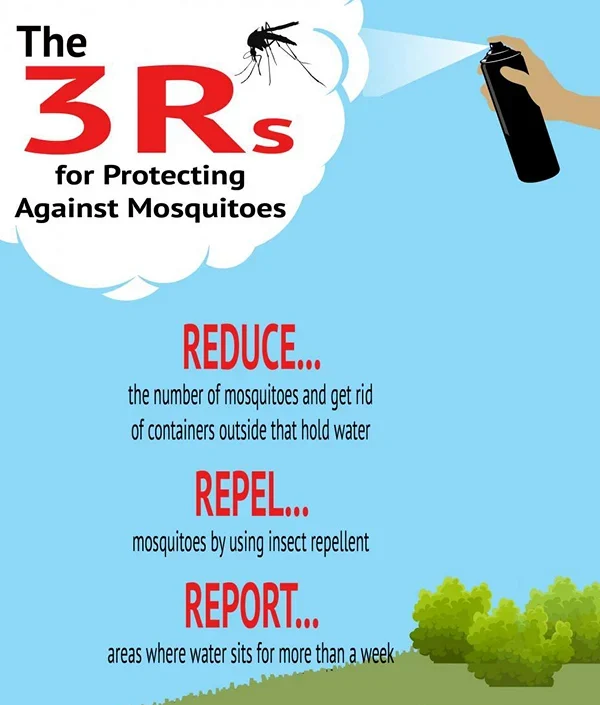

Prevention Strategies: Protecting Yourself and Your Community

Since no vaccine exists for humans, prevention focuses on avoiding mosquito exposure and reducing mosquito populations:

Personal Protection Measures

- Use insect repellent containing EPA-registered ingredients:

- DEET

- Picaridin

- IR3535

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus

- Para-menthane-diol

- 2-undecanone

- Wear protective clothing:

- Long sleeves and pants when outdoors

- Light-colored clothing (less attractive to mosquitoes)

- Consider permethrin-treated clothing for high-risk areas

- Time outdoor activities wisely:

- Avoid dawn and dusk when Culex mosquitoes are most active

- Use extra precautions during peak mosquito season

- Create mosquito-free zones:

- Use window and door screens

- Use air conditioning when available

- Consider mosquito netting over beds in areas without screens

- Use mosquito coils or spatial repellents in outdoor areas

Home and Property Management

- Eliminate standing water where mosquitoes breed:

- Empty and scrub containers holding water weekly

- Clean bird baths and pet water dishes regularly

- Keep swimming pools properly chlorinated

- Cover rain barrels with fine mesh

- Clear clogged gutters

- Fill in tree holes

- Landscape management:

- Keep grass short

- Trim vegetation near the house

- Consider plants that naturally repel mosquitoes

Community-level Prevention

- Mosquito surveillance programs to monitor virus activity

- Public education campaigns

- Larvicide application in public drainage systems and wetlands

- Targeted adult mosquito control when virus activity is detected

- Sentinel animal monitoring (particularly chickens or horses)

These preventive measures are most effective when implemented as a comprehensive strategy involving individuals, households, and public health authorities.

Natural and Home Remedies: Complementary Approaches

While scientific support varies, some natural approaches may complement conventional prevention and treatment:

For Mosquito Prevention

- Essential oils with repellent properties:

- Citronella

- Lemongrass

- Eucalyptus

- Lavender

- Peppermint Note: These typically offer shorter protection than conventional repellents

- Yard and patio solutions:

- Citronella candles or torches

- Fans on outdoor spaces (mosquitoes are weak fliers)

- Mosquito-repelling plants like citronella grass, lavender, and marigolds

For Symptom Relief

For those with mild West Nile fever, certain home remedies may help manage symptoms:

- Fever reduction:

- Cool compresses

- Lukewarm baths

- Adequate hydration

- Pain and discomfort:

- Ginger tea for headaches and body aches

- Turmeric as an anti-inflammatory

- Honey and lemon in warm water for sore throat

- Immune support:

- Foods rich in vitamin C

- Adequate rest

- Stress reduction techniques like meditation

Important note: These complementary approaches should not replace medical care, particularly for anyone with severe symptoms or neurological signs.

Special Considerations for High-Risk Populations

Certain groups require additional preventive measures due to increased vulnerability:

Older Adults (60+)

- Should use mosquito repellent consistently when outdoors

- May benefit from limiting outdoor activities during peak mosquito hours

- Should seek medical attention promptly for any symptoms during WNV season

Immunocompromised Individuals

- May require more aggressive prevention strategies

- Should consider wearing protective clothing even in warm weather

- May need earlier medical evaluation for fever or neurological symptoms

Outdoor Workers

- Should use long-lasting repellents

- May benefit from permethrin-treated uniforms

- Need regular breaks in mosquito-free areas

Pregnant Women

- Should use EPA-registered repellents, which are safe during pregnancy

- May wish to limit outdoor exposure during peak WNV season

- Should inform healthcare providers of potential exposure if symptoms develop

Children

- Should use age-appropriate repellent concentrations

- Should wear protective clothing when possible

- Should not have repellent applied to hands, eyes, mouth, or irritated skin

Tailoring prevention strategies to specific risk factors helps protect those most vulnerable to severe disease.

Global Impact and Surveillance: Tracking the Threat

West Nile Virus has become a global public health concern requiring coordinated surveillance and response:

Surveillance Systems

- Human case reporting: Healthcare providers report confirmed cases to public health authorities

- Mosquito surveillance: Trapping and testing mosquitoes for the virus

- Bird surveillance: Monitoring bird deaths and testing selected birds

- Sentinel animals: Regular testing of chickens or horses in strategic locations

- Climate monitoring: Tracking conditions favorable to mosquito breeding

Economic Impact

The economic burden of West Nile Virus includes:

- Direct medical costs of acute care and long-term rehabilitation

- Vector control program expenses

- Lost productivity from illness and disability

- Impact on blood supply systems requiring screening

- Effects on outdoor recreation and tourism in heavily affected areas

In the United States alone, the cumulative cost of West Nile Virus since its introduction exceeds several billion dollars.

One Health Approach

West Nile Virus exemplifies the need for a “One Health” approach that recognizes the interconnection between human health, animal health, and environmental factors. Effective management requires collaboration across:

- Human health sectors

- Veterinary medicine

- Wildlife biology

- Entomology

- Environmental science

- Urban planning

This integrated approach represents the future of arboviral disease management globally.

Climate Change and West Nile Virus: An Evolving Threat

Climate change is altering the epidemiology of West Nile Virus in several important ways:

Impact of Changing Climate

- Extended mosquito seasons due to warmer temperatures

- Expanded geographic range of vector mosquitoes

- Altered bird migration patterns affecting virus distribution

- Changes in precipitation patterns affecting mosquito breeding habitats

- More favorable overwintering conditions for mosquitoes in previously hostile environments

Projected Trends

Models suggest several concerning possibilities:

- Increased WNV incidence in previously low-risk areas

- More frequent and larger outbreaks

- Potential emergence in new regions globally

- Changes in seasonal patterns of transmission

These projections highlight the need for adaptive public health strategies and continued surveillance as climate change progresses.

Research Horizons: Progress Toward Better Prevention and Treatment

Scientific research continues to advance our understanding and management of West Nile Virus:

Vaccine Development

While a veterinary vaccine exists for horses, human vaccine development faces challenges:

- Multiple candidate vaccines have undergone early-phase trials

- Challenges include the sporadic nature of outbreaks and the primary affected population (older adults)

- Several promising approaches continue in development

Therapeutic Research

Ongoing investigations into potential treatments include:

- Monoclonal antibody therapies targeting the virus

- Antiviral compounds that inhibit viral replication

- Immunomodulatory approaches to reduce neurological damage

- Novel mosquito control technologies

Vector Control Innovations

Emerging technologies with potential impact include:

- Gene drive systems to suppress mosquito populations

- Biological control using Wolbachia bacteria

- New formulations of mosquito larvicides with reduced environmental impact

- Smart mosquito traps with real-time monitoring capabilities

These research directions offer hope for improved WNV management in the future.

Conclusion: Living with West Nile Virus in a Changing World

West Nile Virus has established itself as a permanent part of the disease landscape across much of the world. While most infected individuals never develop symptoms, the potentially devastating impact on those who develop neuroinvasive disease underscores the importance of continued vigilance, research, and public education.

By understanding the virus’s transmission cycle, recognizing symptoms, implementing preventive measures, and supporting both personal and community-level interventions, we can reduce the burden of this disease. As climate change alters patterns of transmission and creates new challenges, adaptive strategies and continued scientific innovation will be crucial.

The story of West Nile Virus reminds us of the complex interconnections between human health, animal populations, and environmental factors—and the need for integrated approaches to emerging infectious diseases in our increasingly connected world.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Can I get West Nile Virus from another person?

A: No, West Nile Virus is not transmitted through casual contact with infected individuals. The virus spreads primarily through the bite of infected mosquitoes. Very rare cases of transmission have occurred through blood transfusion (before screening was implemented), organ transplantation, from mother to baby during pregnancy or breastfeeding, and laboratory exposures.

Q: How long after a mosquito bite would symptoms appear?

A: Symptoms typically develop 2-14 days after being bitten by an infected mosquito. Most commonly, symptoms appear within 3-6 days of infection.

Q: If I’ve had West Nile Virus, can I get it again?

A: Most evidence suggests that people who have recovered from West Nile Virus develop long-lasting immunity against the disease. Reinfection appears to be extremely rare. However, as with many viruses, immunity may wane over many years, and the protection may not be absolute.

Q: How is West Nile Virus different from other mosquito-borne diseases like Zika or dengue?

A: While all are transmitted by mosquitoes, they differ in several ways:

- Different viruses: West Nile belongs to the flavivirus family, as do dengue and Zika

- Different mosquito vectors: West Nile primarily spreads through Culex mosquitoes, while Aedes mosquitoes spread dengue and Zika

- Different symptoms: Zika often causes mild illness but can cause birth defects; dengue can cause hemorrhagic fever; West Nile more commonly affects the nervous system

- Different geographic distributions, though climate change is altering these patterns

Q: Is there a vaccine for West Nile Virus?

A: Currently, there is no approved vaccine for humans against West Nile Virus. Vaccines do exist for horses. Several human vaccine candidates have undergone early clinical trials, but none have yet been approved for general use.

Q: How effective are mosquito repellents against West Nile Virus?

A: Properly applied EPA-registered repellents are highly effective at preventing mosquito bites and reducing West Nile Virus risk. Products containing DEET, picaridin, IR3535, oil of lemon eucalyptus, para-menthane-diol, or 2-undecanone provide the most reliable protection. The effectiveness depends on proper application, concentration, and reapplication according to the product instructions.

Q: Can my pets get West Nile Virus?

A: Yes, animals can be infected with West Nile Virus. Horses are particularly susceptible and can develop severe disease similar to humans. Dogs and cats can be infected but rarely show clinical signs. Birds are the primary amplifying hosts and can become ill or die from the infection. Veterinary vaccines are available for horses.

Q: Should I report dead birds I find?

A: Many public health departments track West Nile Virus by testing dead birds, particularly crows, jays, and ravens, which are highly susceptible to the virus. Check with your local health department about their surveillance program and reporting procedures. Some areas have active bird surveillance programs, while others have discontinued them after the virus became established in the region.

Q: Does having West Nile fever protect me from developing the more severe neuroinvasive disease?

A: If you develop West Nile fever, you will not progress to neuroinvasive disease from that same infection. The neuroinvasive form typically develops rapidly after infection rather than following a mild case. Once you recover from any form of West Nile Virus infection, you likely have long-term immunity against the virus.

Q: Are mosquito dunks and larvicides safe to use in water features on my property?

A: Mosquito dunks and larvicides containing Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis (Bti) or similar biological agents are generally considered safe for use in ornamental ponds, rain barrels, and other water features. They specifically target mosquito larvae while having minimal impact on other organisms, making them environmentally friendly options for mosquito control. Always follow the manufacturer’s instructions for proper application and safety precautions.

ALSO READ MORE HEALTH ARTICLES FROM CHIID HEALTH