The following symptoms or indicators may be experienced by those suffering with bone sarcoma. People with bone sarcoma may or may not have any of these alterations. Alternatively, the origin of a symptom could be a medical disease other than cancer.

When a bone tumor grows, it presses on healthy bone tissue and might damage it, resulting in the symptoms listed below:

Pain: The first signs of bone sarcoma are pain and swelling in the area where the tumor is present. At initially, the pain may come and go. Later on, it may become more severe and consistent. Movement may aggravate the pain, and there may be edema in adjacent soft tissue. The discomfort may not go away, and it may occur while you are sleeping or resting. The majority of bone sarcomas in children develop around the knees and are frequently misinterpreted as “growth pain,” resulting in a delay in diagnosis.

Limping: When a tumor-infected bone in the leg breaks or fractures, it might cause a noticeable limp. Limping is typically an indication of advanced bone sarcoma.

Swelling joints and stiffness: A tumor near or in a joint can cause the joint to enlarge, become tender, or stiff. This means that a person’s range of motion may be restricted and unpleasant.

Other symptoms: People with bone sarcoma may experience symptoms such as fever, general malaise, weight loss, and anemia, which is a low level of red blood cells.

Please consult your doctor if you are concerned about any changes you are experiencing. In addition to other questions, your doctor will inquire how long and how frequently you have been experiencing the symptom(s). This is done to assist in determining the cause of the condition, which is referred to as a diagnostic.

If cancer is discovered, symptom relief is an important element of cancer care and treatment. This is known as palliative care or supportive care. It is frequently initiated shortly after diagnosis and continues throughout treatment. Make an appointment with your health care provider to discuss your symptoms, especially any new or changing symptoms.

STAGES AND GRADES OF BONE CANCER

Staging describes where the cancer is present, whether or not it has spread, and whether or not it is impacting other sections of the body.

Doctors utilize diagnostic tests to determine the stage of cancer, therefore staging may not be complete until all of the tests are completed. Knowing the stage assists the doctor in determining the best course of treatment and can help estimate a patient’s prognosis, or possibility of recovery. Distinct forms of cancer have different stage descriptions.

TNM system of staging

The TNM system is one technique that clinicians use to describe the stage. Doctors use diagnostic test and scan results to address the following questions:

- Tumor(T): What is the size of the main tumor? Where can I find it?

- Node(N): Has the cancer spread to your lymph nodes? If so, where are they and how many are there?

- Metastasis(M): Is the cancer in other parts of the body? If so, where and how much has it spread?

The results are aggregated to establish each person’s cancer stage. Most primary bone sarcomas are classified into five stages: stage 0 (zero) and stages I through IV (1 through 4). The stage provides a common language for doctors to describe the cancer so that they can collaborate to determine the best treatments.

More information on each component of the TNM system for bone sarcoma can be found below:

Tumor (T)

The “T” plus a letter or number (0 to 4) is used in the TNM system to describe the size and location of the tumor. The size of a tumor is measured in millimeters (cm). A centimeter is approximately the width of a normal pen or pencil.

Stages can also be subdivided into smaller groups to assist describe the tumor in greater detail. The following table summarizes tumor stage information for bone sarcoma.

Skeleton, skull, trunk, and facial bones

TX: The primary cancer cannot be evaluated.

T0: There is no indication of a primary tumor.

T1: The tumor is 8 centimeters (cm) or less in size.

T2: The tumor is larger than 8 cm.

T3: There are many tumors in the primary bone location.

Spine

TX: The primary cancer cannot be evaluated.

T0: There is no indication of a primary tumor.

T1: The tumor is exclusively seen on one segment of the vertebrae or on two neighboring segments of the vertebrae.

T2: The tumor is only found on three neighboring vertebrae.

T3: The tumor is located on four or more adjacent vertebrae, or it is present on vertebrae that are not adjacent to each other.

T4: The tumor has spread to the spinal canal or major blood arteries.

- T4a: The tumor has encroached on the spinal canal.

- T4b: The tumor has grown into the major blood vessels or is interfering with blood flow.

Pelvis

TX: The primary cancer cannot be evaluated.

T0: There is no indication of a primary tumor with extraosseous extension.

T1: The tumor is exclusively found in one area of the pelvis.

- T1a: The tumor is 8 cm or less in size.

- T1b: The tumor is larger than 8 cm.

T2: The tumor is exclusively found on one side of the pelvis with extraosseous extension or on two sides of the pelvis without extraosseous extension.

- T2a: The tumor is 8 cm or less in size.

- T2b: The tumor is larger than 8 cm.

T3: The tumor is located in two different areas of the pelvis, with extraosseous expansion.

- T3a: The tumor is 8 cm or less in size.

- T3b: The tumor is larger than 8 cm.

T4: The tumor is located on three different sections of the pelvis or it has crossed the sacroiliac joint, which connects the bottom of the spine to the pelvis.

- T4a: The tumor has spread to the sacral neuroforamen and has involved the sacroiliac joint.

- T4b: The tumor has grown around blood vessels or is interfering with blood flow.

Node (N)

The letter “N” in the TNM staging system denotes lymph nodes. These little, bean-shaped organs aid in the battle against infection. Regional lymph nodes are lymph nodes located near the site of the malignancy. Lymph nodes located in other sections of the body are referred to as distant lymph nodes. Bone sarcomas usually do not spread to the lymph nodes.

NX: The lymph nodes in the region cannot be evaluated.

N0: The cancer has not spread to the lymph nodes in the surrounding area.

N1: The cancer has progressed to the lymph nodes in the surrounding area. This is unusual in the case of primary bone sarcoma.

Metastasis

The letter “M” in the TNM system indicates if the cancer has moved to other parts of the body, a condition known as distant metastasis.

M0: The cancer has not spread.

M1: The cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

- M1a: The cancer has spread to the lungs.

- M1b: The cancer has spread to other bones or an organ.

Grade (G)

Doctors also classify this sort of cancer based on its grade (G). When viewed under a microscope, the grade describes how much cancer cells resemble healthy cells.

The malignant tissue is compared to healthy tissue by the doctor. In healthy tissue, numerous different types of cells are clustered together. If the cancer resembles healthy tissue and contains distinct cell groupings, it is referred to as “well differentiated” or a “low-grade tumor.” When malignant tissue differs significantly from healthy tissue, it is referred to as “poorly differentiated” or a “high-grade tumor.” The grade of the cancer may help the doctor forecast how rapidly it may spread. In general, the lower the grade of the tumor, the better the prognosis.

GX: The grade of the tumor cannot be determined.

G1: The cancer cells have a high level of differentiation (low grade).

G2: Cancer cells have a modest level of differentiation (high grade).

G3: Cancer cells are not well differentiated (high grade).

Cancer stage grouping

Stage IA: The tumor is of low grade or cannot be graded (G1 or GX) and is 8 cm or less (T1). It has not spread to any of the lymph nodes or other regions of the body (N0, M0).

Stage IB: The tumor is of low grade or cannot be graded (G1 or GX) and is larger than 8 cm (T2), or there are several tumors in the primary bone location (T3). It has not spread to any of the lymph nodes or other regions of the body (N0, M0).

Stage IIA: The tumor is of high grade (G2 or G3) and 8 cm or less in diameter (T1). It has not spread to any of the lymph nodes or other regions of the body (N0, M0).

Stage IIB: The tumor is of high grade (G2 or G3) and measures more than 8 cm in diameter (T2). It has not spread to any of the lymph nodes or other regions of the body (N0, M0).

Stage III: Multiple high-grade (G2 or G3) tumors exist at the original bone site (T3), but they have not progressed to any lymph nodes or other regions of the body (N0, M0).

Stage IVA: The tumor has spread to the lung(s) and is of any size or grade (any G, any T, N0, M1a).

Stage IVB: The tumor is any size or grade and has spread to the lymph nodes (any G, any T, N1, or any M), or the tumor is any size or grade and has spread to a bone or organ other than the lung (any G, any T, any N, M1b).

Recurrent cancer: Recurrent cancer is cancer that has returned after treatment. If the cancer returns, more tests will be performed to determine the degree of the recurrence. These tests and scans are frequently identical to those performed at the time of the first diagnosis.

Patients with the best prognosis, on average, have:

- A tumor of low grade (G1).

- A tumor that is easily removed through surgery, such as one found in the arm or leg.

- A tumor that has not migrated beyond its original location.

- Certain genetic mutations

DIAGNOSIS OF BONE CANCER

Many tests are used by doctors to detect or diagnose cancer. They also perform tests to see whether the cancer has spread to another place of the body from where it began. This is referred as as metastasis. Imaging studies, such as x-rays, may be performed to diagnose bone sarcoma and determine whether the disease has spread. Images of the inside of the body are produced via imaging tests. On imaging examinations, benign and cancerous tumors typically appear differently, as detailed below.

Although imaging tests may imply bone sarcoma, a biopsy will be taken whenever possible to confirm the diagnosis and determine the subtype. A biopsy is the only approach to obtain a conclusive diagnosis of cancer in the majority of cases. If a biopsy is not possible, the doctor may recommend alternative tests to aid in the diagnosis. It is critical for a patient to consult with a sarcoma specialist, such as an orthopedic oncologist, before undergoing any surgery or biopsy.

Not all of the tests described below will be administered to every individual. When selecting a diagnostic test, your doctor may take the following variables into account:

- The type of cancer that is suspected.

- Your age, as well as your overall health.

- The outcomes of previous medical tests.

The following tests, in addition to a physical examination, may be performed to diagnose or identify the stage (or extent) of a bone sarcoma:

Blood test: Some laboratory blood tests may aid in the detection of bone sarcoma. Alkaline phosphatase and lactate dehydrogenase levels in the blood may be elevated in people with osteosarcoma or Ewing sarcoma. It is crucial to note, however, that high levels do not usually indicate cancer. When cells that create bone tissue are particularly active, such as when children are developing or a damaged bone is healing, alkaline phosphatase levels are generally high.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): An MRI produces detailed images of the body by using magnetic fields rather than x-rays. The tumor’s size can be determined via an MRI. To provide a crisper image, a special dye known as a contrast medium is administered before to the scan. This dye can be injected into the vein of a patient. MRI scans are used to look for malignancies in soft tissue nearby. MRIs provide a map for the orthopedic oncology surgeon to follow in order to do the best cancer surgery feasible.

Computed tomography (CT) scan: A CT scan uses x-rays captured from various angles to create images of the inside of the body. A computer combines these images to create a detailed, three-dimensional image that identifies any anomalies or malignancies. A CT scan can be performed to determine the size of the tumor. To improve image detail, a specific dye known as a contrast medium is sometimes administered before to the scan. This dye can be injected into a patient’s vein or given to them in the form of a pill or liquid to consume.

Bone scan: A bone scan can assist determine the stage of a bone sarcoma. A bone scan examines the inner of the bones using a radioactive tracer. The tracer is injected into the vein of a patient. It accumulates in bone regions and is detected by a particular camera. Healthy bone appears lighter to the camera, but regions of harm, such as those caused by malignant cells, stand out.

X- ray: An x-ray is a technique that uses a small amount of radiation to create a picture of the structures inside the body.

Positron emission tomography(PET) scan: A PET scan can aid in determining the stage of a bone sarcoma. A PET scan is frequently coupled with a CT scan (see above), resulting in a PET-CT scan. However, your doctor may refer to this technique simply as a PET scan. A PET scan is a technique for creating images of organs and tissues within the body. A radioactive sugar compound is put into the patient’s body in modest amounts. This sugar molecule is absorbed by the cells that consume the most energy. Cancer absorbs more radioactive stuff because it aggressively uses energy. The material is then detected by a scanner, which produces images of the inside of the body.

A biopsy is the removal of a small sample of tissue for microscopic examination. Other tests can indicate the presence of cancer, but only a biopsy can provide a definitive diagnosis. The material is next examined by a pathologist (s). A pathologist is a medical professional who specializes in interpreting laboratory tests and assessing cells, tissues, and organs to identify disease. The location of the cancer determines whether a needle biopsy or an incisional biopsy is performed. A small hole is created in the bone during a needle biopsy, and a tissue sample is extracted from the tumor using a needle-like tool. The tissue sample is extracted during an incisional biopsy after a small cut is made in the tumor. It is not always possible to do a biopsy.

Patients should be examined in a sarcoma speciality facility even before the biopsy is performed because the type of biopsy and how it is performed are critical in identifying and treating sarcoma. The treating surgeon at the sarcoma center can choose the best spot for the sample. Because bone sarcomas are uncommon, it is also critical to have an expert pathologist analyze the tissue sample retrieved in order to properly diagnose a sarcoma.

TREATMENT OF BONE CANCER

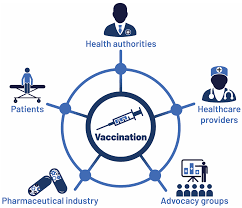

Different types of specialists frequently collaborate in cancer care to develop a patient’s overall treatment plan, which mixes many sorts of therapy. This is referred to as a multidisciplinary team. Other health care professionals on cancer care teams include physician assistants, nurse practitioners, oncology nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists, social workers, pharmacists, counselors, nutritionists, and others.

The following are descriptions of the most prevalent types of therapies for primary bone sarcoma. Primary bone sarcoma is a type of cancer that begins in the bone. Treatments for symptoms and side effects, which are an important element of cancer care, are also part of your treatment plan.

Treatment options and recommendations are influenced by a variety of factors, including the kind, stage, and grade of cancer, potential side effects, and the patient’s preferences and overall health. Take the time to read about all of your treatment options, and don’t be afraid to ask clarifying questions. Discuss the aims of each treatment with your doctor, as well as what you can expect during treatment. These discussions are known as “shared decision making.” When you and your doctors collaborate to choose therapies that meet the goals of your care, this is referred to as shared decision making. Because there are various treatment choices for bone sarcoma, shared decision making is very crucial.

The primary treatment for a low-grade primary bone tumor is surgery. The purpose of surgery is to remove the tumor as well as a margin of good bone or tissue around it to ensure that all cancer cells are removed.

Doctors frequently utilize a mix of treatments to treat a high-grade primary bone tumor. Among these include surgery, systemic therapy with medications, and radiation therapy.

Surgery

Surgery is the removal of the tumor and some surrounding healthy tissue during an operation. Surgical oncologists and orthopedic oncologists are doctors who specialize in treating bone sarcoma using surgery.

Surgery for bone sarcoma often involves a wide excision of the tumor. A wide excision means that the tumor is removed, along with a margin of healthy tissue around it in all directions. Before surgery, talk with your health care team about the possible side effects from the specific surgery you will have.

When a tumor is located in an arm or leg, procedures to preserve the arm or limb are used whenever possible. This is also known as “limb salvaging” or “limb sparing.” However, amputation, or the removal of the arm or leg containing the tumor, is sometimes required. This is determined by the size and/or location of the tumor.

Amputations for persons with bone sarcoma have been minimized thanks to wide excision surgical procedures. Rather than amputation, more than 90% of patients can be treated with limb-sparing surgery. Limb-sparing procedures frequently necessitate the use of prostheses, such as metal plates or bone from other regions of the body, to replace missing bone and strengthen the remaining bone. This is referred to as reconstructive surgery. Surgeons cover the rebuilding region with soft tissue, such as muscle. The tissue promotes healing and lowers the chance of infection.

Amputation may be the best option for treating sarcoma in some people. These persons include those whose sarcoma is in a location where surgery cannot entirely remove it, patients who cannot undergo reconstruction, and patients whose surgical region cannot be properly covered with soft tissue.

Prostheses will be required following an amputation. Some youngsters can be fitted for expandable joint prosthesis that adjust as the skeleton grows since their bones are often still growing. Several surgeries are required to alter bone length as the youngster develops with these prostheses.

Surgery may also be used to treat bone sarcoma that has spread to other parts of the body, a condition known as metastasis. For example, surgery can be useful in eliminating lung metastases, which are the most common site of bone sarcoma dissemination. Surgery has a great possibility of treating the condition if there are few tumors in the lung and they arise a long period after the main bone tumor was removed.

It is crucial to remember that the procedure that results in the most usable and strongest limb may not be the same as the one that results in the most normal appearance. Rehabilitation can be quite beneficial following bone sarcoma surgery. This includes physical treatment, which can help the patient maximize his or her physical ability. Rehabilitation can also help a person cope with the social and emotional consequences of surgery, such as the difficulties of losing a limb if amputation is required. Discuss your support choices with your medical team.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of medications to eradicate cancer cells, typically by preventing the cancer cells from growing, dividing, and proliferating.

A chemotherapy regimen, or schedule, typically consists of a predetermined number of cycles administered over a predetermined time period. A patient may be administered one medicine at a time or a mixture of drugs at the same time. Chemotherapy for bone sarcoma is typically administered as an outpatient treatment, meaning it is administered at a clinic or doctor’s office rather than in a hospital.

Surgery is frequently insufficient treatment for some forms of bone sarcomas, including osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. Cancer cells that escaped from the primary tumor can cause these tumors to reappear as distant metastases, most commonly in the lungs. Chemotherapy has extended the lives of persons with some kinds of bone sarcoma. Furthermore, chemotherapy is frequently used to treat cancer that has already spread visibly at the time of diagnosis.

Chemotherapy is frequently used before surgery to treat fast-growing bone sarcomas. Preoperative chemotherapy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, or induction chemotherapy are all terms used to describe chemotherapy administered prior to surgery. The oncologist may prescribe chemotherapy for 3 to 4 cycles before surgery for most high-grade malignancies in order to reduce the main tumor or make it easier to remove.

Chemotherapy prior to surgery may also help people live longer lives because it kills cancer cells that have spread from the initial tumor. The tumor’s response to chemotherapy can be used to improve prognosis. To assess the efficacy of the chemotherapy, tumor cells are examined under a microscope after the original tumor has been removed to determine what proportion of cells were killed. This is known as the necrosis factor.

After the patient has recovered from surgery, he or she may be given further chemotherapy to kill any leftover tumor cells. This is known as adjuvant or postoperative chemotherapy. Chemotherapy used before surgery to reduce the tumor, followed by chemotherapy after surgery, has saved many lives and limbs.

The chemotherapy medications utilized are determined by the type of bone sarcoma. Each variety of bone sarcoma is distinct, just as breast cancer is distinct from lung cancer. Here is a list of medications that are commonly used to treat two of the most frequent kinds of bone sarcoma.

The following medications are commonly used to treat osteosarcoma:

- Cisplatin (available as a generic drug)

- Doxorubicin (available as a generic drug)

- Methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall)

The following medications are commonly used to treat Ewing sarcoma:

- Cyclophosphamide (Neosar)

Chemotherapy side effects vary depending on the individual and the dose used, but they can include exhaustion, infection risk, nausea and vomiting, hair loss, loss of appetite, and diarrhea. These adverse effects normally fade away once the treatment is completed. However, your doctor will keep an eye on you for any long-term negative effects.

Radiation therapy

The use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to eliminate cancer cells is known as radiation therapy. A radiation oncologist is a doctor who specializes in the use of radiation therapy to treat cancer. External-beam radiation therapy, which delivers radiation from a machine outside the body, is the most prevalent method of radiation treatment. Internal radiation therapy, also known as brachytherapy, is a type of radiation therapy that uses implants to deliver radiation. A radiation therapy regimen, or schedule, typically consists of a predetermined number of treatments administered over a predetermined time period.

Radiation therapy is most commonly used for bone sarcoma tumors that cannot be removed surgically. Radiation therapy can be used before or after surgery to reduce the tumor or to eradicate any leftover cancer cells. Radiation therapy allows for less invasive surgery, often preserving the arm or leg. As part of supportive or palliative care, radiation treatment may also be utilized to reduce discomfort in patients (see below).

Radiation therapy might cause fatigue, moderate skin responses, upset stomach, and loose bowel motions. The majority of negative effects fade quickly after treatment is completed.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a type of cancer treatment that targets specific genes, proteins, or the tissue environment that contributes to cancer growth and survival. This method of treatment inhibits cancer cell growth and spread while limiting damage to healthy cells.

The targets of all cancers are not the same. Your doctor may order tests to determine the genes, proteins, and other variables in your tumor in order to find the most effective treatment. This enables clinicians to provide the most effective treatment to each patient whenever possible. Furthermore, research studies are continuing to learn more about specific molecular targets and new treatments aimed at them.

A mutation in the neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase (NTRK) gene is found in less than 1% of sarcomas. Larotrectinib (Vitrakvi) is an NTRK inhibitor that is now approved for any tumour with a specific NTRK gene mutation. Fatigue, nausea, dizziness, vomiting, elevated liver enzymes, cough, constipation, and diarrhea are the most prevalent side effects.

Discuss with your doctor the potential side effects of a certain medicine and how to manage them.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy, also known as biologic therapy, is intended to increase the body’s natural defenses against cancer. It employs components created by the body or in a laboratory to enhance, target, or restore immune system activity.

Immunotherapy is not commonly recommended for the treatment of sarcomas, particularly bone sarcomas, because it has not been thoroughly evaluated. “Immune checkpoint inhibitors” are used in many recently approved immunotherapy treatments for other forms of cancer. These medications are administered to the patient in order to suppress the body’s natural immune response against cancer.

Current immunotherapy treatments have limitations since these medications can trigger immune responses against normal body parts, a phenomenon known as autoimmunity. Some of these medications are already approved to treat other types of cancer. However, if testing on your bone tumor reveals that it has specific problems repairing DNA damage, known as microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR; this occurs in less than 1% of sarcomas), a checkpoint inhibitor such as pembrolizumab (Keytruda) or dostarlimab (Jemperli) can be used.

Different forms of immunotherapy might result in a variety of adverse effects. Skin rashes, flu-like symptoms, diarrhea, and weight fluctuations are all common adverse effects. Consult your doctor about the potential adverse effects of the immunotherapy that has been prescribed for you.